[Please read last week’s letter to catch up, if you haven’t already!]

So. Why else might producers utilize a fake, omniscient robot in their reality show? We as viewers are becoming more aware of producers’ hijinks, which is partially due to tell-all books and podcasts. Some of the intel comes from participants and producers describing their experiences, while some information is just outsider analysis.

Recommendation break! There’s an excellent book called How to Win the Bachelor (and an accompanying podcast, “Game of Roses”) which provides excruciating detail and statistics on all of the Bachelor seasons up through early 2022. It really pulls back the curtain and shows how much of a machine the show is, while illustrating what contestants can do to take advantage of said machine. I can’t express how much fun the book is to read, even if you’ve never seen an episode of the show; it’s analytical, funny, example/data-driven, in on the joke, and so insightful. It’s both loving and critical in all the right ways.

Because of the public’s increasingly watchful eye, shows are rebranding as “experiments” and “lessons,” as I mentioned last week. This is the full circle result of shows like Fear Factor or Survivor, which I’ll call Category 1 Shows, which transparently torture/challenge their contestants for a chance at money. The journey is openly unpleasant (usually physically), and players opt in knowing what they’ll face. Explicit competition shows, Category 2, hover in between the two poles. They promise contestants not just money but something better—love, a record deal, a modeling contract—and players aren’t always fully aware of the hardships in store. The shows are framed as talent-rewarding competitions which happen to be televised, rather than entertainment which happens to be talent-themed.

In Category 3, it’s not enough for a show to entertain; just as corporations now “stand for something. (Eye roll. For more, see: rainbow capitalism, greenwashing, etc.) These shows pretend that their main goal is to spiritually benefit their participants. In this “didactic”/“scientific” genre, contestants might be promised moral betterment or a life partner. If talent competitions present themselves as almost charitable, sincerely rewarding hard work, these shows present themselves as philosophical. It’s up for debate whether this is even what viewers want, or if it’s just what producers think we want to see. After all, I don’t know that anyone really believes that Love is Blind is revolutionary science, and I’d rather watch contestants straightforwardly gossip than hear them talk about why the Very Legitimate Experiment has changed their outlook on life forever. (Why do producers bother trying to convince us that they’re backed by psychology or are revolutionary? I’d watch the exact same show if they never claimed any scientific validity.)

On the flip side, many viewers want contestants to have some sincere motivation for going on the show. If you’ve watched reality TV, you’ve heard the phrase “here for the right reasons,” which is code for “not just here for fame and money.” Sometimes money isn’t even involved, because the likelihood that they’ll receive a lucrative online following is its own currency. When contestants enter into shows, it’s often with some sense of how reality shows operate and what the tropes are. Therefore, producers need a way to A) avoid being seen as abusive and B) navigate contestants’ desire to control how they are portrayed onscreen. As I mentioned before, a cast member might be wary of a producer’s information, and may have their own agenda with regards to their onscreen persona. So in comes Lana, whose air of science and general bizarreness throws them off their game. Additionally, the audience can see with their own eyes that the contestants are acting of their own accord, in response to what Lana says. There’s a catalyst and a result, so the storyline feels less fabricated.

So, I finally reach reason #4 for Lana the fake robot:

4. Producers get to save face! They also have more influence over the cast. Even if the contestants know that Lana is just a conduit for producers’ whims, she’s faceless, and therefore any producer might be her. Producers can ally with the contestants, against Lana, and maintain the illusion that the show’s main goal is bettering its cast, ratings be damned! Contestants are, at least to some extent, aware that they’re being exploited. Historically, producers have pretended to side with contestants, while harshly—even cruelly—betraying them to stir up good TV. This means that any producer might also be nice and good and want what’s best for you. With Lana present, a producer doesn’t risk getting ratted on by contestant X to contestant Y—Lana is the one who told person X person Y’s secret! It wasn’t me! The vagueness of Lana’s abilities ensures that she can be held responsible for anything and everything, can be hiding in any shadow, and can punish or reward. Producers get to seem hands-off, while Lana is the autonomous scientist who pushes her lab rats toward spiritual awakening. Hands off each other, little lab rats! Lana will take away your money if you don’t start telling each other your deepest secrets on TV!

And now:

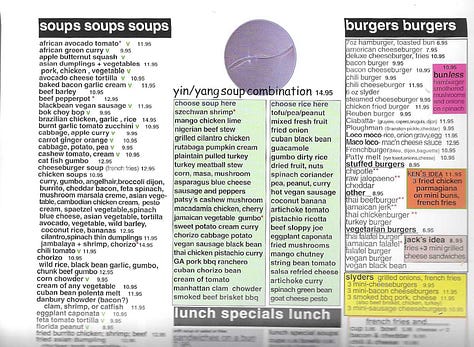

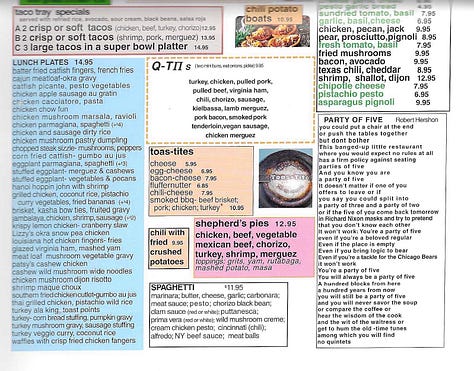

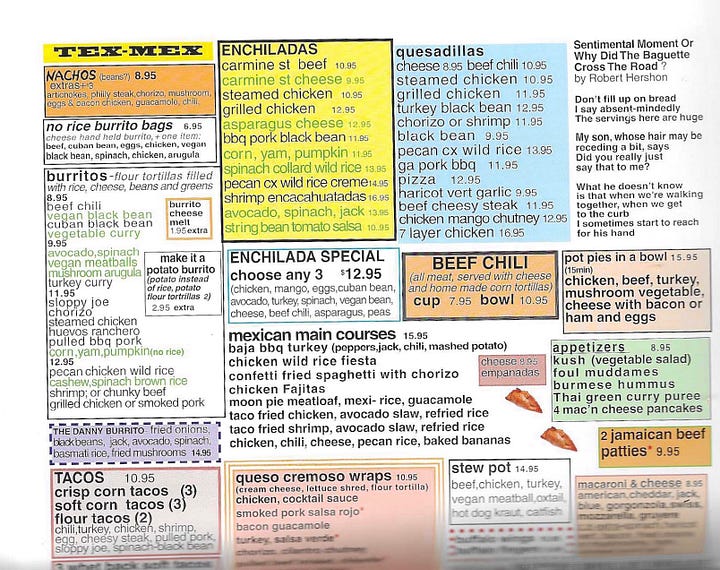

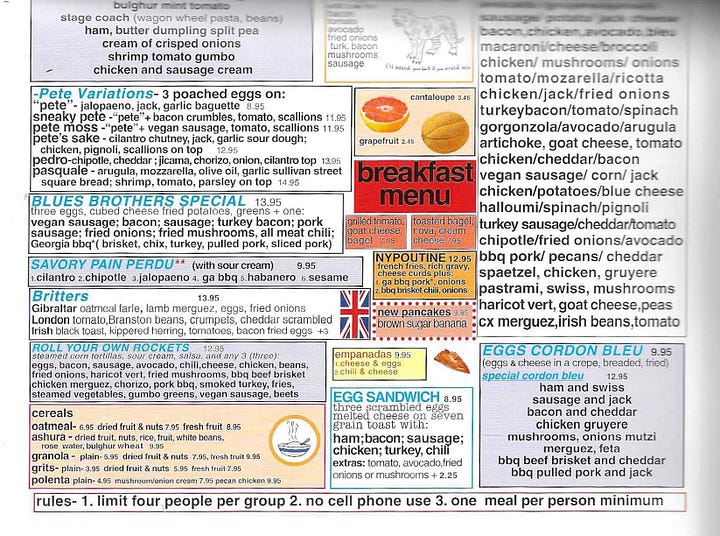

Scans from my copy of Eat Me: The Food and Philosophy of Kenny Shopsin. Shopsin’s is a fantastic restaurant and NYC institution that’s now located in Essex Market on the Lower East Side. (When it opened in the ‘70s, it was on Morton & Bedford in the West Village.) In my last apartment I essentially lived above Essex Market, and would go to Shopsin’s on maaaany a Sunday. It’s a family-run restaurant that was initially led by Kenny Shopsin, whose strong personality and zany-in-a-good-way food fostered the brash/homey/scrappy environment that remains today. Our favorite there, Luke—who recently left :(—has, several times, simply banned me from ordering an item in favor of something better. And he was right every time! Truly carrying on the Shopsin’s legacy.

The Essex location is a bit cramped, so their menu is condensed from its former glory; Shopsin’s was always oriented around its regulars, so many dishes are named after them. I miss Shopsin’s and even have a plate from it, which I auspiciously found at Fish’s Eddy while dishware-hunting for my move to the West Village. Yes I know I only moved a few miles across town! Yes it’s a hop skip & a jump on the F! Let me be! I’m eternally nostalgic!

So without further ado, scans of some of the old menu, so you’re not overwhelmed. The book has recipes and great writing from Kenny. I highly recommend it. Go to Shopsin’s, not that you need me to tell you. And if you have any recommendations for where to find other plates from restaurants, let me know…!

I love you I love you! Bye!