In my last letter, I used my compendium of Sears Roebuck catalogues—in conjunction with my friend’s beautiful objects—to look at how we understand functional items. This week, Sears Roebuck is back.

I was in Japan for the last week and a half or so, and over the first few days, my girlfriend had a mission which included going to a bunch of the used camera stores in Shinjuku. She takes photos professionally & is super into/knowledgeable about cameras; while she was browsing & I was keeping myself entertained, I found (& bought) a camera catalogue from 1999.

When we look at old ads & catalogues, we can glean something a little different from what we’d learn by looking at the advertised items themselves. An old car can tell you one thing, and an ad for that same car will provide a different angle. What were we impressed by and attracted to, not just in the products themselves but in their presentation? With something like a camera, there are only so many forms it can take: at the end of the day, it has to FUNCTION like a camera, and therefore has to look like one too. And sometimes, the “uglier,” the better—utilitarianism can show that more effort went into function than aesthetics.

To this point, there’s been something of a camera boom lately. Or really, in many ways, there’s been an OLD camera boom. People want grainier photos, broken devices that don’t charge quite because they don’t make those batteries much anymore. And in many ways, that desire for older technology reflects the notion of utilitarianism. Cameras are so severely high-def now that the images they give us feel perversely true-to-life. I don’t want to see what my eyeballs see; that’s not interesting anymore, and it’s not always pleasant. I want something not quite accurate. And beauty aside, cameras’ high resolutions somehow circle back around to feeling…un-technological? Photos produced by film—and from bad digital cameras—force you to understand an image within the context of the device it was taken on.

I, and I suspect many people, live in a constant state of I don’t get it and I never really will, so I’ll just figure out how to use it and be comfortable with that about high-level tech. There are too many innovations and there’s so much vague, abstract science. Even using the word “science” for it feels like it outs me as someone with actually no fucking clue how anything works. I can’t tell what’s impressive and what’s not, and there’s not really a way to keep up with it all. At best it’s confusing and at worst, it’s existentially stressful.

Technological intricacies aside: there’s pretty much a ceiling for how cool most people’s personal gadgets can be. Photos used to convey a lot about the devices they were taken on, thereby functioning as an implicit brag—whether about a big investment or general knowledge. But now, a super advanced camera might take photos that look awfully similar to those on your phone. Apple’s years of “Shot on iPhone” campaigns say it all. So we’ve cycled back around. And with everything feeling like software, indecipherable to the point of feeling imaginary, most of us just have to trust that people using the big words are correct.

So doesn’t it make sense that people want to return to a machine that they can make sense of? Obviously the spike in interest in Polaroids, disposable cameras, & crappy digitals have the element of nostalgia and vintagey coolness; we all know that Y2K fashion is huge, Gen Zers love thrifting, etcetera. But I don’t think that accounts for everything! I think I (we!) want to see gears turn. When I look at an image, I want to know that I captured it with a machine that worked hard to give me a result. Tactility offer the feeling of working in tandem with a device, rather than passively using it.

Whereas before, we may have saved our highest-res cameras for special occasions, now the fuzziness of a lower-res photo distinguishes “Moments” from the millions of random photos we take on our phones every day. You can call it all cheesy or wannabe-vintage or fake-deep, or argue that people just want to seem grungy and artistic. That it smacks of the hipstery defiance of 2010s Williamsburg. And that may all be fair! But I think it’s also fair to say that there’s something pleasing in waiting for film to get developed; to know there are limited opportunities to capture what’s in front of you; to glimpse what was, in a different time, the height of advancement.

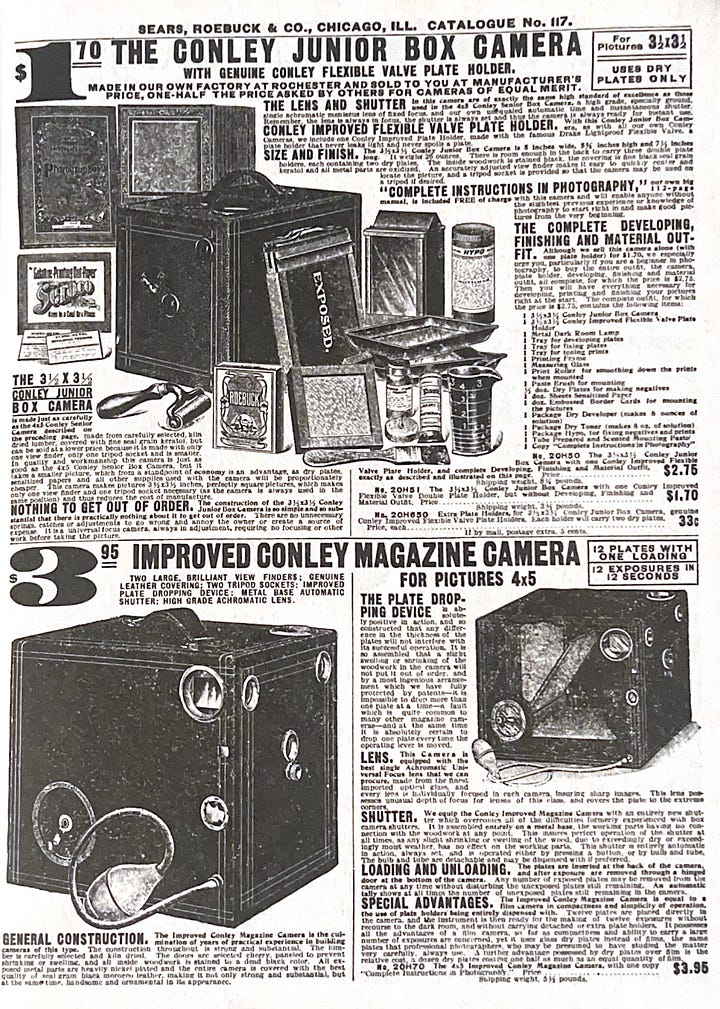

I could talk forever about our relationship with technology, its ubiquitousness, the way companies have invaded it and sucked out the fun, our souring on it all. But I don’t want to. It’s exhausting, too close to home. As with images that too closely resemble real life, ideas that feel so all-consuming just get tiresome and suffocating. Instead: catalogues, from another time & another place.

These pages hold so much, and after a long read, I’ll just let you peruse them for yourselves. How we wanted technology to be presented, how we felt about advancements, mechanics, art, exploring the world—it’s there. Reply to this email letting me know what you find in them all, if you feel like it. I’d love to know.

Love you love you, bye!